I am now coming to you

from Kuajok, Warrap State. Apologies for the long absence in blogging, which

has been due in a large part to irregular access to power. Since my beloved

MacBook battery is on its last legs, writing updates without power has been

very difficult. Now I see why blogging is a luxury of the urban middle class.

Kuajok is the capital

of Warrap State. The first two things that anyone will tell you when you arrive

in Kuajok is that (1) it is a very new town and (2) it has been very well

surveyed. The latter is certainly true. The roads are so straight it would break

the Romans’ hearts to see them. The first thing is technically true – as a

‘town’ Kuajok is new, but it was a mission, schools and was a large village since

1923. President Kiir himself went to secondary school in Kuajok and when he

came on an official visit last week, leaned up to the window of his car and

shot a special “thumbs up” to the group of secondary school students lined up

in their uniform to greet him (much to their delight).

In my first few weeks

here I have been told a lot about the arrival of the missionaries and

establishing Kuajok as a centre. On Wednesday evening I was taken on a walk to

the river port where the missionaries landed (Wanh Abun). At this time of year

the river is about an hours walk away, over toic (flood plain), its still quite

wet and walking is the only way to get there.

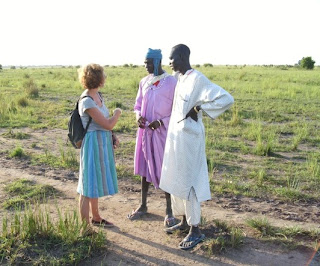

On the way we met

several groups of people heading back to their home villages across the river

after having sold milk, maize in Kuajok market or having just been visiting. My

Dinka language – although still very limited – is now at the stage where I can

have a small conversation, introduce and explain myself to people.

These two young men

were walking to a cattle camp about 4 hours away, but they explained that they

were strong and they would run so it would only take them 2. Young men

frequently like to point out to me how strong they are and tell me how weak I

am (as a foreign girl).

When we got to the

river they swam across it (instead of taking the small boat) after telling me I

would never be able to make it, despite my protestations that I do know how to

swim!

At the river bank, to the left of the boats currently used my commuters is ‘Wanh Abun.’ Essentially a bank, the only thing that marks it out is the 6 or 7 metal posts that were once used to moor the missionaries boats. One of them has been pulled out of the ground and you can see the cast mark of a London company “Siemens”. There is also the remains of a brick structure which an old lady told me was the house of an missionary. To me it looked too small and too close to the river to be a house, more likely a store room connected with the mooring of the boats or a place to rest and unload